Editor's note: In WellNest Watch, master's degree candidates in EMU's College of Health of Human Services explore news, research and standard practices in the field of health and wellness.

Imagine needing urgent care and receiving a bill that derails your finances for years. For millions of Americans, illness doesn’t just take health; it takes stability.

When getting better becomes a debt trap, medical care itself becomes a public health risk. A 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation study found that 41% of U.S. adults currently have medical or dental debt, which translates to roughly 100 million people when applied to the adult population.

That is nearly two in five adults. Many of whom owe lenders, credit card companies, or collection agencies because of hospital bills they couldn’t afford to pay.

The same 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation study reported that about one in three adults, 35%, delayed or skipped needed medical care because of cost. Among adults with medical debt, the share was even higher, at 64% putting off treatment due to financial pressure.

This is not a fringe problem; it is an epidemic of avoidance. And like most epidemics, it hits hardest along existing fault lines. Black and Hispanic households, low-income families, women, and people without insurance are disproportionately burdened. Every unpaid bill becomes another barrier to future care.

Medical debt does more than damage credit scores; it damages health.

A 2024 study, published by the medical journal JAMA Network Open, found that counties with higher rates of medical debt reported more days of poor physical and mental health, along with higher mortality.

Chronic stress, anxiety and depression walk hand in hand with debt. Families skip medications or appointments to stay afloat. In many cases, being sick means choosing which illness to address: the physical one or the financial one. Even after people recover medically, the economic fallout lingers.

Medical debt blocks housing, reduces credit scores and traps families in instability. In public health terms, debt is not just a bill; it is a risk exposure.

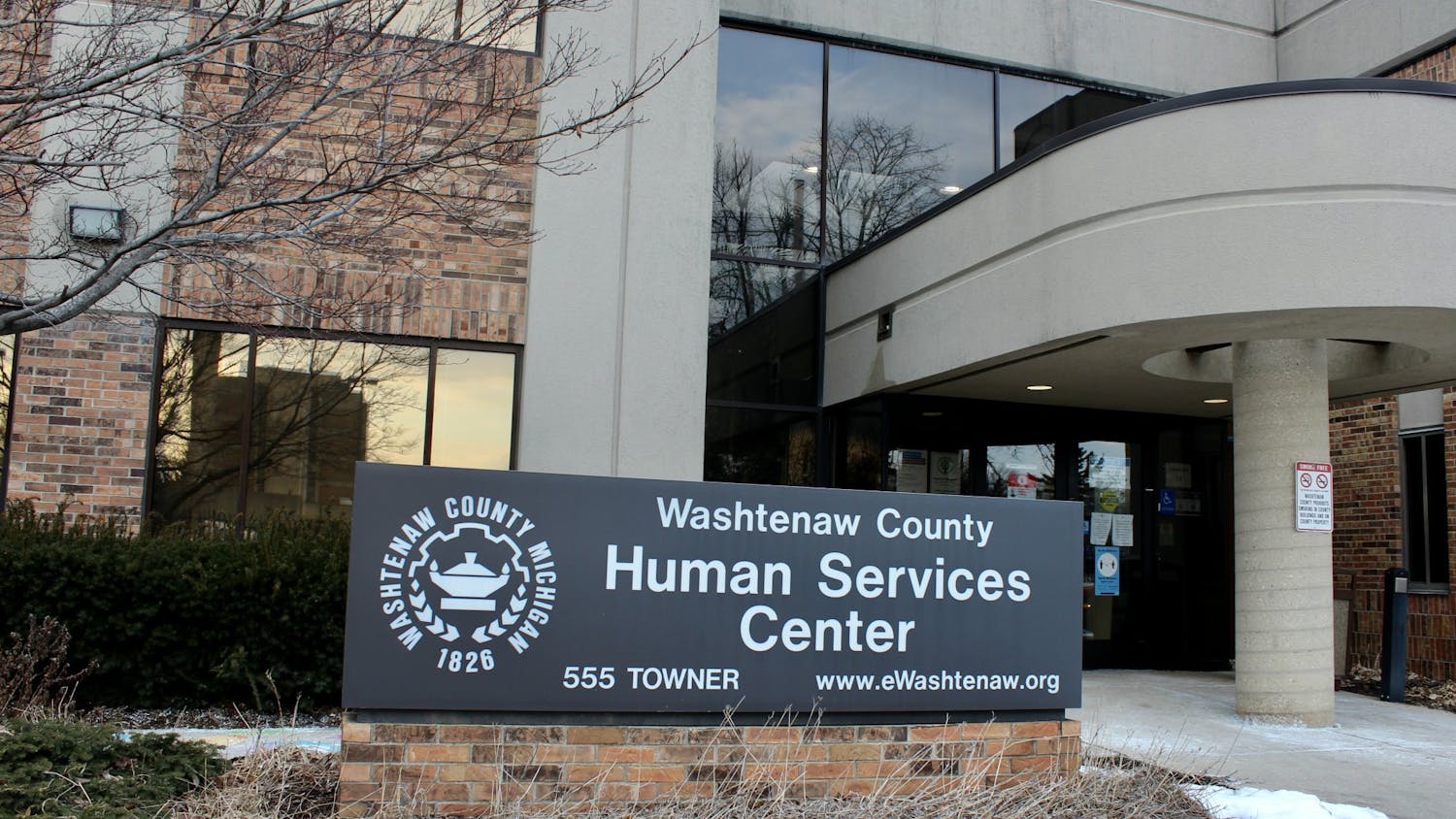

Michigan confronted this reality directly. In July 2025, the state erased $144 million in medical debt for about 210,000 residents through a partnership with the nonprofit Undue Medical Debt. Qualifying residents did not need to apply; the relief was automatic. In Kalamazoo County alone, more than 7,200 people saw $2.4 million in debt wiped out in a single quarter.

In Ypsilanti, where students and families juggle tuition, rent and part-time jobs, an unexpected emergency-room bill can cause real damage. Medical debt does not just shape physical health; it shapes graduation timelines, stress levels and housing stability. Michigan’s action recognizes something long ignored: Debt relief is a public health intervention.

Yet policies meant to protect patients remain unpredictable. In Jan. 2025, federal regulators proposed removing medical debt from credit reports nationwide, only for the rule to be struck down by a court six months later. Protections differ across states and hospitals vary widely in how they screen patients for financial assistance. When basic safeguards can appear and disappear overnight, families remain exposed. Medical debt becomes not only a financial burden but a policy vulnerability.

International comparisons from the Commonwealth Fund’s Mirror, Mirror 2024 report and analysis from the Peterson–Kaiser Family Foundation Health System Tracker show the same pattern: The U.S. spends more on health care than any other high-income country, yet Americans live shorter lives and experience more preventable illness.

Part of this paradox lies in financial toxicity, where the cost of care becomes a disease in itself. Some reforms offer hope. Medicaid expansion reduces medical debt and strengthens financial stability.

The federal No Surprises Act limits unexpected out-of-network bills. State-level bans on medical debt credit reporting, such as in Colorado and New York, have dropped reported collections to zero. But these gains remain uneven and insurance designs continue to push people toward high deductibles and unpredictable billing.

At its core, medical debt represents a failure of prevention: not of biology, but of system design. True prevention means protecting people from both illness and insolvency. Local hospitals can help by automatically screening patients for financial assistance before sending bills to collections. Universities like Eastern Michigan can strengthen support for students who are navigating insurance, billing confusion, and rising healthcare costs. And policymakers should treat financial protection as part of public health infrastructure, as essential as vaccines, clean water, or safe housing.

When illness becomes a bill, recovery is never complete. The debt does not stay on paper; it lives in bodies, minds and neighborhoods. Public health must reclaim its purpose: Preventing harm before it begins, even when that harm arrives in an envelope marked balance due.

About the author: Shafaat Ali Choyon is a public health professional and former business strategist with more than 16 years of cross-sector experience spanning healthcare, technology, advertising, mobile financial services, FMCG, e-commerce and education. He currently serves as a graduate hall director in Housing and Residence Life at Eastern Michigan University and as a consultant for EMU’s Office of Health Promotion.

Contributors to The WellNest Watch health column: Kegan Tulloch and Ebrima Jobarteh, graduate assistants in the Office of Health Promotions; and Shafaat Ali Choyon and Nathaniel King, graduate hall directors in the Department of Residential Life. All four are master's degree candidates in the School of Public Health at Eastern Michigan University.